Discovering Dylan is like being handed the keys to the universe. Once that light goes on suddenly the world seems vastly different than it did before. I have friends who’ll recite Dylan in any situation given half a chance, so it’s not unusual to hear one of them break into Shelter From The Storm at a dinner party for instance.

Discovering Dylan is like being handed the keys to the universe. Once that light goes on suddenly the world seems vastly different than it did before. I have friends who’ll recite Dylan in any situation given half a chance, so it’s not unusual to hear one of them break into Shelter From The Storm at a dinner party for instance.

For all the justifiable attention the man gets as a wordsmith, his skills as a melodic songwriter are all too often overlooked. Songs like I Shall Be Released or Every Grain Of Sand are carried by such beautiful melodies they can raise your spirits or cut straight to your heart. How odd then that a man who has the capacity to stir our hearts, souls and minds with such passion and emotion should be in possession of what David Bowie once described as “a voice like sand and glue”. But such are the power of his songs Dylan quickly became idolised and indeed lionised by the folk movement.

Even though I was born in the 60’s I didn’t truly come to appreciate Dylan until my teens in the mid 70’s. As a young kid I distinctly remember the incredible power of Blowin’ In The Wind with its plea for love, compassion and tolerance as it raised some incredibly telling questions about the behaviour of the human race. But it was Peter, Paul and Mary’s version that was played on the radio, not Bob’s – though even as a little kid I was still aware of who Bob was. My parents weren’t well educated or politically engaged, but it seemed pretty much everyone knew of Bob Dylan.

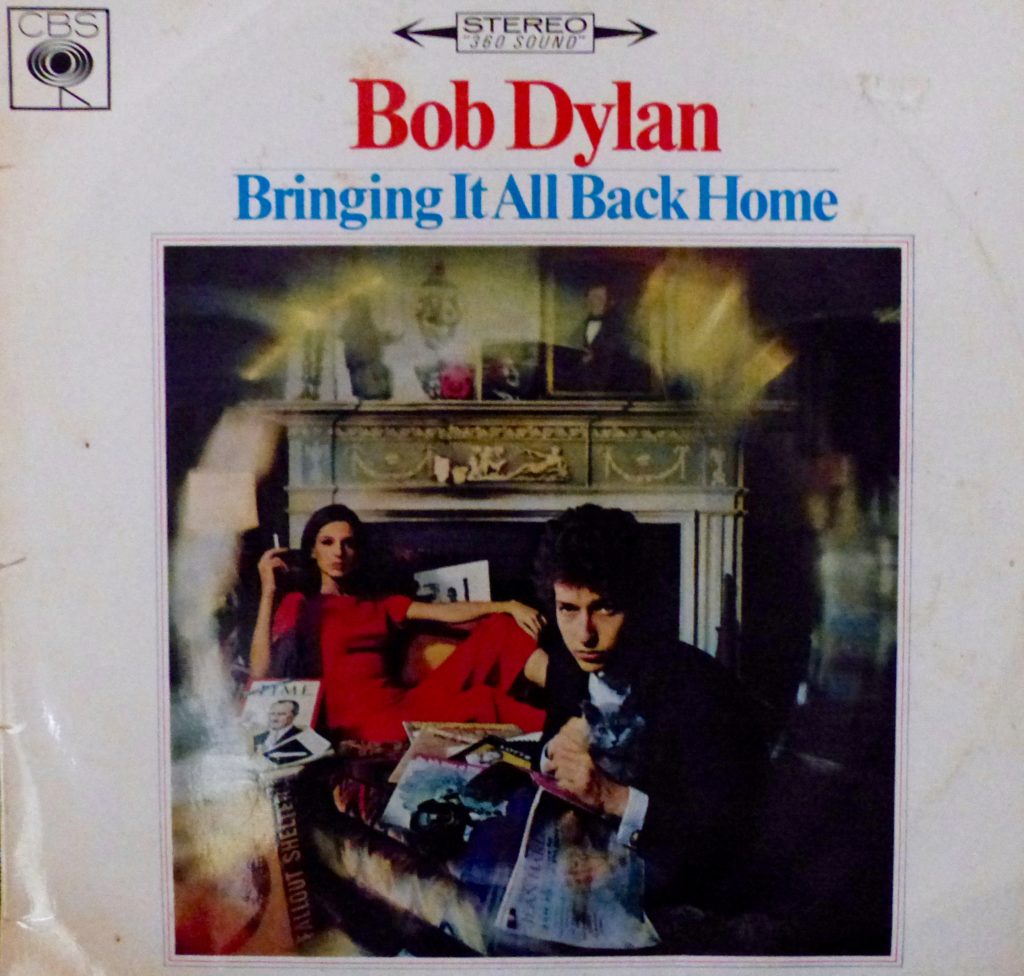

I can’t recall that there was a particular song or album that turned me on to Bob, because I was already well versed in many of his best known songs thanks to my older brother’s copy of Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits (1967). What I do know is that once I started to explore the wider world of music (as teenagers do) in the mid 70’s I developed a deeper appreciation for Dylan, in particular albums like Highway 61 Revisited, Blood On The Tracks and Bringing It All Back Home – an album predominantly influenced by the blues.

For the folkies who had claimed Dylan as their prophet (if not their God), Bringing It All Back Home must have been their equivalent of Armageddon. Just a year earlier with the release of The Times They Are A Changin’ Dylan had cemented his place as the critical conscience of social injustice and the champion of the down trodden, but as he began to feel the weight of expectation with which he’d been burdened he began to question the very movement that had crowned him with such reverent fervour.

While the transitional album between these two records Another Side Of Bob Dylan (released late 64) had already flagged a shift in direction for the Mighty Zim with less politicised and more personal songs it was Bringing It All Back Home that was the real game changer. The times were indeed a changin’ – the British were coming and they were bringing their electric guitars with them. This album was Bob’s get out of jail free card from the confines of folkdom and his unwanted standing as the chosen one.

Bringing It All Back Home was notoriously split into an electric side and an acoustic side with seven songs on the electric (first) side and four acoustic tracks taking up the flip side. Such an arrangement wouldn’t raise a sniff today, but back in 65 when this album was released it was a huge controversy. A few months after this album was released Dylan played his first live electric set and was booed by sections of the crowd. The fact that Dylan chose the Newport Folk Festival to premiere his electric show says a lot about Bob’s attitude to the folkies that were claiming he’d betrayed the cause of their music.

Even when you remove the electric controversy Bringing It All Back Home was a revolutionary record for Dylan. Lyrically it was out there, like really out there. The directness of his earlier songs of social conscience were gone, replaced by more personalised criticisms and abstract lyrics that were intriguing and beguiling, yet somehow Bob spoke to a generation like never before.

When you think of the timeless Dylan classics that predate this record like Blowin’ In The Wind, The Times They Are A Changin’, A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall or Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright it’s staggering when you realise that Bob hadn’t scored a top 40 hit in his native U.S.A until this album. What’s even more absurd is the song that made it happen was so anti establishment it must have rocked those in charge right down to their head kicking boots. Subterranean Homesick Blues hits you with a rant that perfectly tapped into the paranoia of the times:

The phone’s tapped anyway

Maggie says that many say

They must bust in early May

Orders from the D.A.

And this:

Look out kid

It’s something that you did

God knows when

But you’re doing it again

As Bob says:

You don’t need a weatherman

To know which way the wind blows.

Subterranean Homesick Blues was way ahead of its time. Stylistically it was a precursor to rap – only more revolutionary, insightful and concise. The song was also one of the very first to have a promotional film shot for it, pre-dating MTV by a decade and a half.

After the breakthrough of Subterranean Homesick Blues (all the way up to #39 on the charts!) strangely the album’s centrepiece and one of Dylan’s most beloved songs Mr. Tambourine Man failed to make a dent in the U.S, although The Byrds’ version released soon after sailed psychedelically on its magic swirling ship all the way to the top spot. The song had been around for a while before it was included on this album with Bob performing it live as early as mid 64 – as he did in the version below at the Newport Folk Festival.

Dylan saves much of his vitriol on the album for the establishment – not those in government, but those running (or ruining) the folk movement. Outlaw Blues (I might look like Robert Ford, but I feel just like Jesse James); Maggie’s Farm (Well I try my best to be just like I am/But everybody wants you to be like them/They sing while you slave and I just get bored); and his farewell to the folkies It’s All Over Now Baby Blue (Strike another match, go start anew/And it’s all over now Baby Blue).

Gates of Eden rings with the cynical disenchantment of the troubadour who now questions not only authority, but all he sees in this world. The twisted truth of war and peace, the fate of all to fall with a crashing, but meaningless blow; and the kingdoms of Experience rotting in the precious wind, for there are no truths outside the gates of Eden.

The compelling It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding), is one of Dylan’s finest songs. The heady, hypnotic rhythm of the song’s tempo combined with its lyrical spray create a stream of consciousness effect, yet Dylan couldn’t have been any clearer with the intent of his message. He’d had a gutful of the lionising of the cult of who he was supposed to be, but this wasn’t the angry rage of a young artist bemoaning the price of celebrity, it was a brilliantly articulated plea for reason and rationale, because:

Even the President of the United States

Sometimes must have to stand naked.

There are insights into how frightening it must have been to encounter those who felt they owned him:

You lose yourself, you reappear

You suddenly find you got nothing to fear

Alone you stand with nobody near

When a trembling distant voice unclear

Startles your sleeping ears to hear

That somebody thinks they really found you.

Then it’s as if his mind is thinking out loud as he reassures himself:

A question in your nerves is lit

Yet you know there is no answer fit to satisfy

Insure you not to quit

To keep it in your mind and not forget

That it is not he, or she, or them, or it

That you belong to.

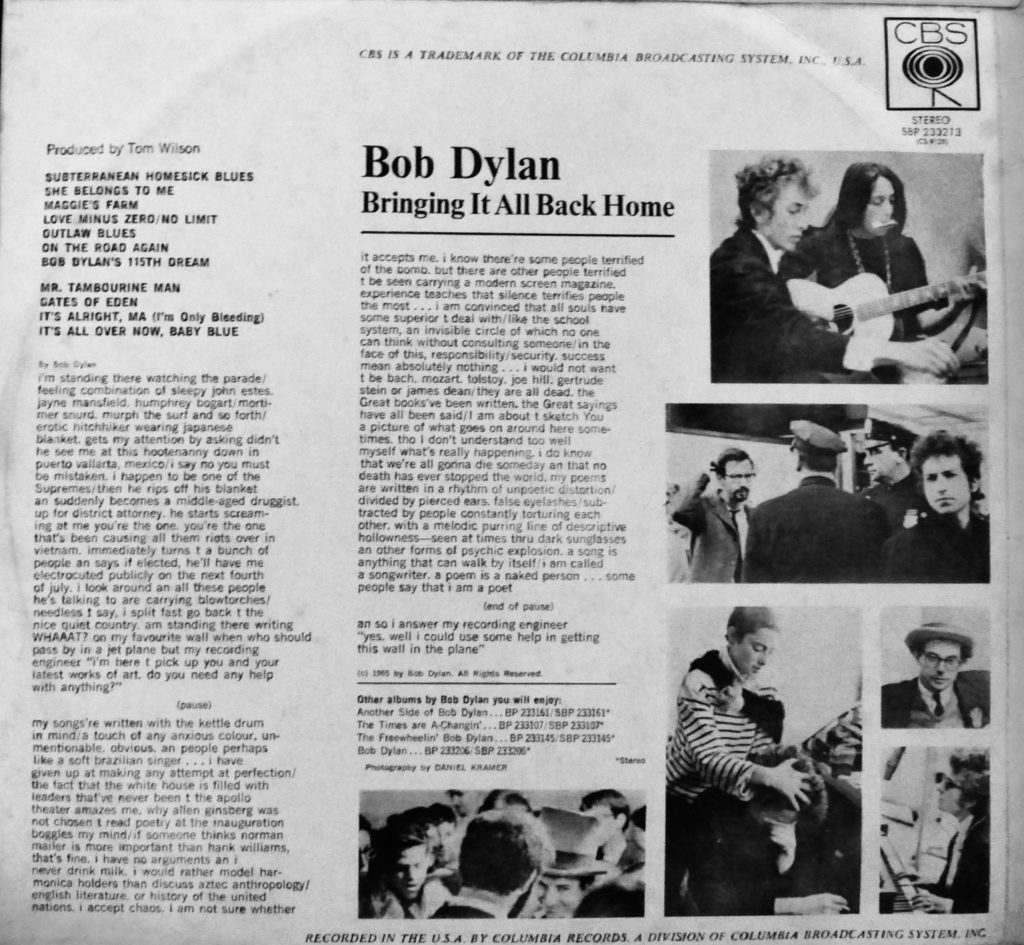

There can never be any doubt about who was Bringing It All Back Home. It was Dylan attempting to bring it all back to where he started, his raison d’etre. To reclaim who he was and to do it on his own terms. You didn’t need the lyrics of his songs to tell you that, Bob’s liner notes on the back of the album said as much. It’s all wrapped up in the riddling mystery of Bobspeak, but he refers to “watching the parade” and then when approached by a stranger Dylan says it must be a case of mistaken identity. Humorously Bob tries to convince the antagonist he’s actually one of The Supremes, as the man screams at Dylan “you’re the one, you’re the one!” and then goes on to blame him for “causing those riots over in Vietnam” as an angry mob on a witch hunt carrying blowtorches surrounds him.

I can’t begin to imagine how terrifying the prospect of trying to live up to his unwanted mantle as the voice/oracle/saviour of a generation must have been for Bob. It’s just nuts when you think about it, but then these were turbulent times in America. Dylan may have reclaimed his identity, but as he withdrew from the glare of the public eye he became more of an enigma and the cult of his eminence as the twentieth century’s greatest songwriter would only continue to grow with successive releases in the years that followed. Perhaps, in the end, none of us can ever really go back home, not even Bob.

Some Primo Dylan Cuts From Sound Distractions:

Thank You Music Man, for the walk down memory lane. I was about 16 when these songs were popular, and the poetry still touches me in a deep way. My Mr. Tamborine Man left a couple of years ago, He went through the 60’s in the late 70’s, as he was busy studying law in the 60’s??!! Your writing is quite insightful, even from the next generation, and a different country. Interesting for me. Rings true, “Don’t hate anything except hatred.” Marty Foster

As Bob wrote so succinctly “he not busy being born is busy dying”. We all need to keep growing and it’s something both you and your Tamborine Man have done with such passion and ongoing curiosity. Thanks for your generous praise Marty. x