The early Police albums encapsulate a time in my mid teens that tapped into my boundless energy and unbridled enthusiasm for just about everything. There’s a wide-eyed openness in our young lives that seems a little naïve on reflection, yet the shortcomings we possessed through our inexperience were compensated by our willingness to embrace promising new concepts with optimistic fervour. One of the amazing aspects of music is that long after we’ve lost touch with how we felt at any given moment in our past lives, it allows us to recall, and even tap back into those emotions.

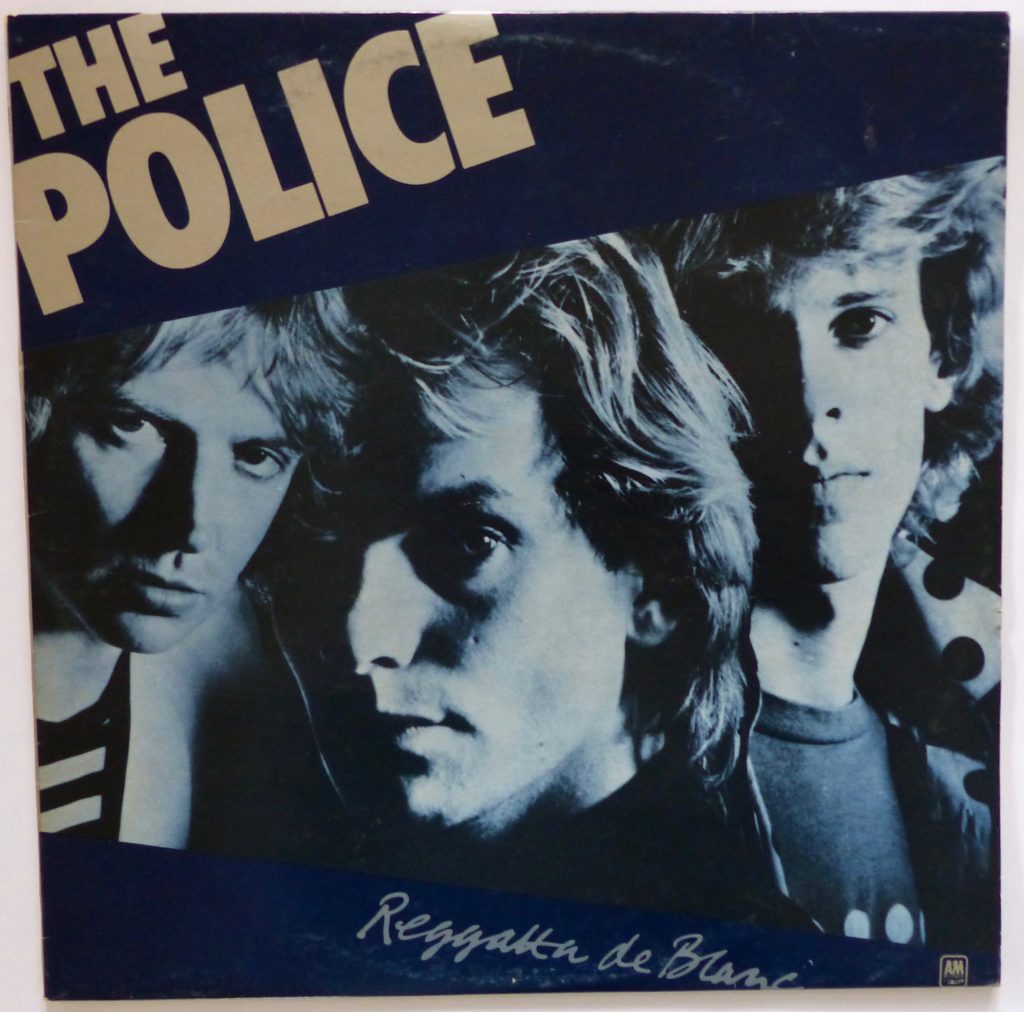

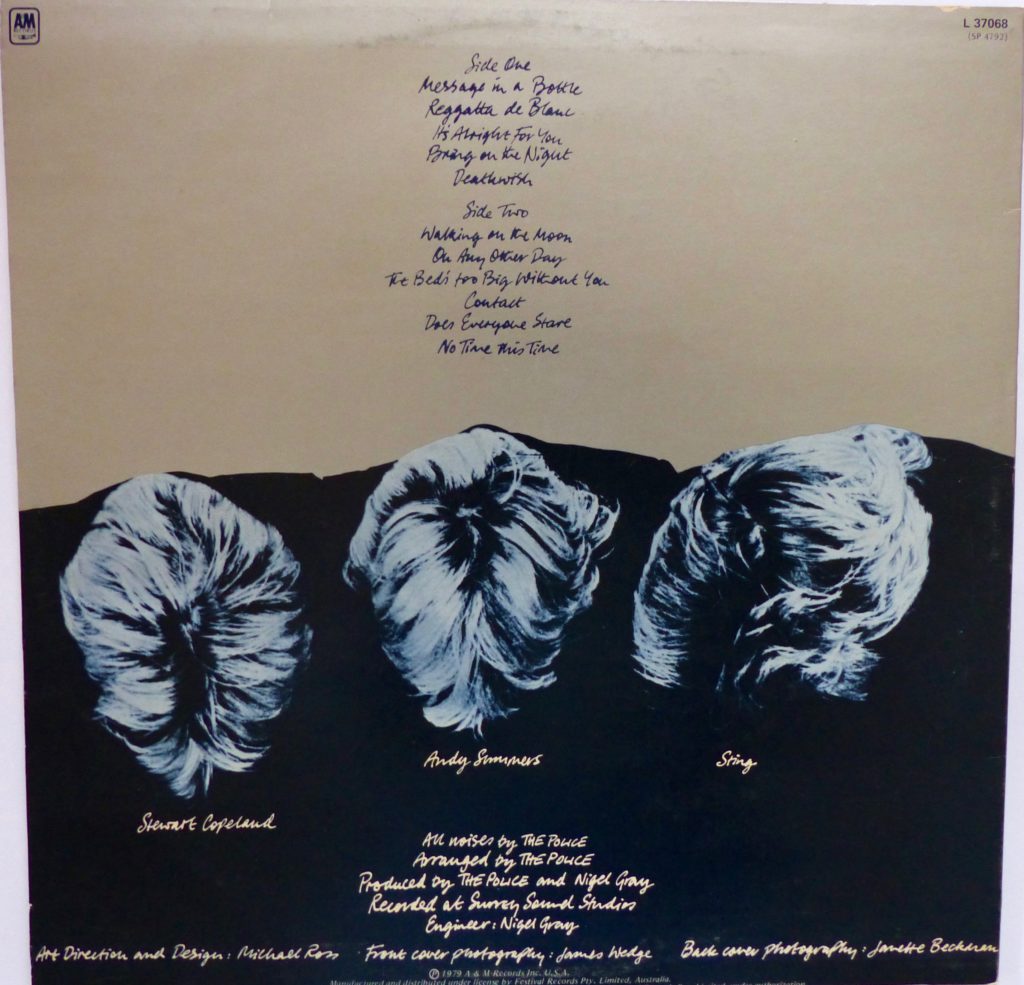

Of all those early Police records Regatta de Blanc is the one that never fails to capture the spirit of my youth. There was an excitement to this band in the late 70’s and early 80’s that dwindled over the years as their songs were increasingly thrashed on MOR radio playlists across the planet. Of course that’s not the band’s fault, but then the power of those songs have also been undermined somewhat by Sting, who in his later years became so much a part of the establishment, embodying the aspects of celebrity he publicly detested on a song like Peanuts from the band’s debut Outlandos d’Amour. Take a line from that song like “Don’t want to read about the love your making” and then think of his ridiculous tantric sex quote years later. Guilty as charged.

I don’t know why it’s this particular Police album that does it for me. Sure, the album’s two big hit singles Message In A Bottle and Walking On The Moon are undoubtedly two of their finest (though strangely neither of them were a hit in the U.S.), but there were so many other stand out tracks on the record as well. Beyond that there’s something undefinable about this album, it’s about a feeling more than anything else, or more to the point, the way it makes me feel.

Message In A Bottle kicks in with all the urgency you’d expect from a band whose sensibilities had been shaped by the punk movement. Stewart Copeland’s drumming and Andy Summers’ looping guitar riff drive the momentum and Sting doesn’t waste any time jumping in with a directness that spells out exactly what’s going on from the opening line: “Just a castaway, an island lost at sea – oh”. Interestingly it’s the verses that carry the tempo, not the chorus, which slows down to little more than a few beats from Copeland and Sting’s slightly detuned bass line – all serving to emphasise the song’s main message “I’ll send a message to the world, I hope that someone gets my message in a bottle”. At least we think it’s the point of the song, until the twist in the last verse “Seems I’m not alone in being alone, a hundred billion castaways looking for a home” and then the penny drops as everyone of us who has ever felt alienated (like every teenager glued to the song) realises that yes, these guys understand, they get it.

So after such an impressive opening where do you go next? Well an instrumental of course – so much for following the classic rock album track listing manual. The title track Regatta de Blanc (loosely translated as “White Reggae”) has Copeland playing at his percussive best with Summers’ playing that swirling riff that became the template for so many Police songs to follow. At just over 3 minutes it’s just getting started by the time it robs us way too short of the mark, but then It’s Alright For You is the kind of song that can’t be held back with the majority of the songs lines consisting of only two words:

Wake up

Make up

Bring it up

Shake up

Stand by

Don’t cry

Watching while the world die

You only have to see those lyrics jump off the page to know that this ain’t no power ballad.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4pXGPF8tnl4

Bring On The Night ensures the album’s energy if not tempo is maintained. One of the band’s best songs, that Sting later used brilliantly as part of a medley with When The World Is Running Down, You Make The Best Of What’s Still Around for the opener to his solo live set Bring On The Night in the mid 80’s. The original studio version here opens with one of Andy Summers’ great rhythmic riffs before Stewart Copeland’s bass drum kicks in with solitary beats progressively quickening as the fade in gets louder to create an effect like the song is fast approaching you from a distance. It’s such a stunning and effective intro that Fleetwood Mac’s Stevie nicked it for her fab solo effort Edge Of Seventeen a couple of years later. Two for the price of one – a killer intro goes a long way. Lyrically, even allowing for Sting’s borrowed T.S. Eliot phrase “the evening spreads itself against the sky”, he still leaves his mark with lines like “The future is but a question mark, hangs above my head there in the dark”. The back end of the song tails out with numerous vocal repeats of the song’s chorus but there’s still plenty to admire here in the instrumentation, particularly the stellar guitar work from Summers’ as he fires off his trademark riffs – not so much playing his axe, more like stabbing it with great effect.

Spot the difference. Bring On The Night v Edge Of Seventeen.

Deathwish is a sonic adventure that sounds like it was born from a jam. With the song getting a rare writing credit for all 3 band members there’s every chance that’s exactly what it was and seems a fitting way to close out the side.

Flipping the vinyl over to start side two reveals one of finest recorded moments from The Police and is one of the best examples of the band’s forte – the use of space. As a three piece the dynamics of sound within your arrangements are so much more pointed, there simply isn’t any room to hide, but that also means you can build that sound to critically highlight each instrument or element within the track. In the case of Walking On The Moon, for a song so diligently arranged it begins inauspiciously, with a little amplifier hum as if Summers or Sting had only just remembered to plug his guitar in at the last second as the tape began to roll with the added clunkiness of some shuffling background noise in the studio. But Copeland’s syncopated hi hat is already tapping out the time as Sting’s beautiful bass line rolls into play. Then it’s the chiming of Summers’ singularly strummed reverberating chord as the bass drum kicks in with a more prominent beat. It all happens within the first 15 seconds of the song and you suddenly realise your listening to three craftsmen who know exactly what they’re doing. I never tire of listening to this song, it really is timeless. When Walking On The Moon first came out my mates and I were convinced the song was written when the band were stoned on weed and the subsequent slow mo effects of their movements gave rise to the song, though Sting has said he wrote it when he was drunk. I’m not sure if that says more about me and my mates, or that Sting was more of a bore than we realised at the time.

Stewart Copeland gets a rare lead vocal outing next on the amusing On Any Other Day, before the band jumps into full white boy reggae mode with Bed’s Too Big Without You. Again, it’s one of those great album tracks that elevate this record to the band’s best. In this case what could have been a simple reggae knock off becomes far more interesting with Andy Summers’ combination of a snaking guitar lead and trademark chopped guitar riffs. Throw in Copeland’s wonderful percussion along with Sting’s dub bass line and you’ve got a Jaffa of a song.

The next two numbers on Regatta de Blanc were both penned by Stewart Copeland. Contact concerns a suspicious lover who’s been jilted and accordingly has a darker musical tone, while Does Everyone Stare stands out a mile on the disc as a piano led piece. The latter was apparently written years earlier and included on Regatta because of record company pressure to get the album out as quickly as possible to cash in on the success of Outlandos d’Amour. For the Police their lack of material was exacerbated by the slowness of their debut to take off in the first place and the endless touring to promote that album in building their fan base. While Outlandos had been released in 1978 they didn’t get any traction with it on either side of the Atlantic until the following year and by the time it broke through Regatta was released just a few months later. It’s incredible in hindsight that a song that is now considered a classic like Roxanne had to be released several times before radio began to play the song before it finally took off.

Regatta de Blanc closes with another older song that was originally the B side to So Lonely. Regardless, No Time This Time is a ripper of a track with an energy that typified the New Wave sound. It has all the urgency of a punk song, minus the attitude. This is not a song of frustration for the disaffected youth, it’s one for their older siblings struggling to make their way in an increasingly hectic world:

No time for the complexities of conversation

No time for smiles, no time for knowing

No time for the intricacies of explanation

No time for sharing, even less for showing

Its pedal to the metal stuff with Andy, Sting and Stewart all going flat out and one hell of a way to finish this fabulous album. Given the intense pressure they were under to produce Regatta de Blanc it’s a remarkable result. With the exception of one or two songs it’s an incredibly consistent record and arguably their best. After years of touring and the slow start to the success of their debut, perhaps more than anything else this follow up was fuelled by the band’s optimism, with at long last a realisation of their potential and the possibilities that lay ahead. Much like the sentiments of my generation who latched on to it.

Leave a Reply