It’s the summer holidays and I’m in the heart of Midnight Oil’s turf on Sydney’s northern beaches. The house where I’m staying is just off Powder Works Road, the winding piece of bitumen that paved the way down to the coast and brought the wax heads from the city’s leafy north shore and beyond down to the nirvana of one of Sydney’s best breaks. It’s also the road that gave name to Midnight Oil’s independent record label when they began in the late 70’s.

It’s the summer holidays and I’m in the heart of Midnight Oil’s turf on Sydney’s northern beaches. The house where I’m staying is just off Powder Works Road, the winding piece of bitumen that paved the way down to the coast and brought the wax heads from the city’s leafy north shore and beyond down to the nirvana of one of Sydney’s best breaks. It’s also the road that gave name to Midnight Oil’s independent record label when they began in the late 70’s.

Yesterday I had a few beers at the pub where the Oils took up residence and laid the foundations of their fanatical following. In those days it was called the Royal Antler, a sticky carpeted joint that reeked of stale ale and sweat on Narrabeen’s beachfront. Today it’s known as The Sands, a soulless box of new steel, concrete and glass buried under a few storeys of apartments that’s as far removed from what its name now suggests as the idea of what a classic Sydney pub should be.

Midnight Oil always put on a hell of a show, as did their fans at those early gigs. Fights would spontaneously erupt as (mostly) surfers fuelled on beer, weed and speed would frenetically pogo across the floor, arms flailing as they’d slam into each other with the inevitable consequences. Long before mosh pits evolved in the grunge era, an Oils crowd was one big heaving mass of testosterone surging, contorting and contracting like the ocean waves the band and their fans lived to ride. A fight would break out in one place only to transmute like a swarm across the floor as new combatants were sucked into the fray. To be honest I couldn’t hack that madness, I wanted to see the band on my own terms from the relative sanity of the back of the room without being belted, bruised and bloodied by a barrage of elbows, fists and heads.

The Oils were loud and uncompromising with the relentless energy and reckless enthusiasm of a punk band, but far more potent than most in articulating their message. It didn’t hurt that they had a fiercely impassioned and balding lead singer almost 2 metres tall to deliver it. Peter Garrett was an imposing front man with a distinctly manic dancing style that was often mimicked by fans. Indigenous injustice, the environment, corporate greed, corruption and US foreign policy became synonymous with Midnight Oil’s music and while Garrett was a formidable mouthpiece those issues could never have cut through as effectively as they did without the incredible music from this immensely gifted band of players. Rob Hirst was a powerhouse behind the kit, as well as being a superb song writer and vocalist. Jim Moginie possessed a creatively adventurous musicality as a composer as well as being a talented multi-instrumentalist – skills that would later serve him well as a producer. With Martin Rotsey sharing guitar duties alongside Jim Moginie and Peter Gifford on bass completing the line up the Oils were an indomitable force to be reckoned with.

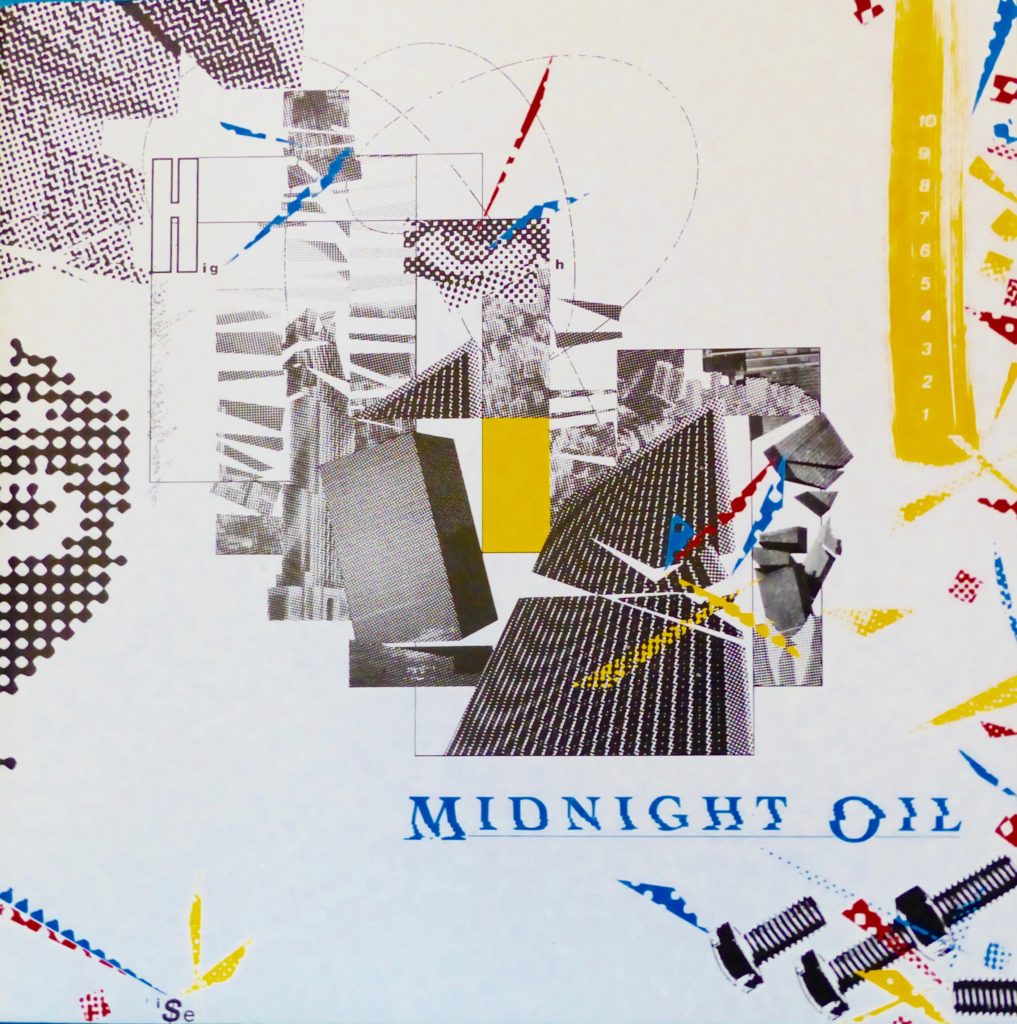

10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 was a massive turning point for Midnight Oil. Their previous 3 albums had cemented their place as one of Australia’s foremost alternative hard rock acts and while their live following continued to grow they were still largely ignored by the commercial media. Not that it bothered the Oils, these guys marched to the beat of their own drum, but that beat changed significantly with 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1.

The album was recorded in September 82 at London’s Townhouse Studios with a ridiculously young Nick Launay at the helm on production duties. At just 21 it was one of the first albums Launay produced and as a relatively unknown quantity it says a lot about Midnight Oil’s willingness to take risks and dive into unknown waters at this crucial point in their career.

The band discarded their previous methodology of trying to capture their intoxicating live sound on record in favour of integrating new digital technologies and industrial sounds into their hard rock sound. Where previous albums had thundered with propulsive energy and aggression 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 throbbed and pulsated with funky bass lines and electronic beats. In this experimental electric soup guitars cracked with menacing distortion on tracks like Scream In Blue while Rob Hirst’s drumming took on a new percussive precision among those electro beats. The result was a heady, exciting and totally new sound not only for Midnight Oil, but rock music.

The album’s intriguing opener Outside World with Peter Gifford’s pulsating bass, Jim Moginie’s eerie keyboard and Rob Hirst’s random percussion deals with isolation and exploitation (possibly indigenous?). As a slow and weird reveal it’s an unlikely entrée to such a dynamic record but when the song morphs into Only The Strong we’re suddenly jolted into the explosive entity of the Oils at their best. It’s here that Launay lays down the template and tempo for the identity of the album that follows. Just as the track gets going it comes to a halt as Garrett spits out the song’s existential frustration of “one more day of eating and sleeping” with a discordant guitar strum as the line’s punctuation mark before Gifford’s irresistible strutting bass line kicks in. Garrett winds up the angst with “Speak to me, speak to me, I’m at the edge of myself, I’m dying to talk” and with it he articulates the frustration of a generation who just want to scream when they’re locked in their rooms.

By the time the menacing Short Memory snakes into play with Gifford’s fat bass line the Oils are at their raging political best ripping into US foreign policy and imperialism. The song is a mini masterpiece, brilliantly arranged with sharp guitar and piano exchanges intermittently before Garrett rips into a verbal rage, all the while the song keeps its sinister groove right up to its final blast. Read About It then fires up with a tirade on the exploitation of the working classes (under both capitalism and communism); the agendas of governments and their foreign policies; the failure of media reportage; and living in the shadow of the bomb:

Another little flare up

Storm brewed in a teacup

Imagine any mix up and the lot would go

Has there ever been a more scathing and terrifying song to dance to? I think not.

Scream In Blue opens with a distortion of guitars before moving into an experimental hybrid of rhythm and noise until the song comes to an abrupt halt and Peter Garrett sings a haunting vocal that’s ominously Orwellian:

“Be careful what you say, there’s enough noise in this” and “I could kill for this one time and not get caught”.

It’s a sobering if not entirely clear end to the first side of the album that fires up again with the side two opener US Forces. The song’s stunning introduction is typical of Launay’s production on the album with plenty of space around the instrumentation to create maximum impact. On US Forces it’s the simple strumming of 2 acoustic guitars made to sound unbelievably big with incredible clarity juxtaposed against the blast of Moginie’s solitary synthesiser ringing in your ears that sets up another stinging attack on US foreign policy:

“US forces give the nod, it’s a setback for your country”.

The Oils serve up a stark reminder of the times with the ever present nuclear threat during the Cold War; Reaganomics: “Now market movements call the shots” (sadly just as true today as it was then); and the stupidity of Scientology – sorry folks but the Oils were right: “L. Ron Hubbard can’t save your life”. The song’s dynamic duelling rhythm guitars make you want to get up and dance, but should we be doing it while Rome is set to burn?

Then the throb of the Power & the Passion with its pointed critique on the apathy that was “the temper of the times” kicks in. The song’s metronomic drum beat is the perfect rhythm for the mindless masses on remote control:

“Take all the trouble that you can afford

At least you won’t have time to be bored”

Again, it’s Peter Gifford’s bass line that gives the song it’s fabulous groove. Rob Hirst drills an inspired drum solo into the mix while Rotsey and Moginie’s guitar interplay provide foils to the rhythm until a supercharged horn section carries the song to its dramatic conclusion.

Nowhere was Midnight Oil more lyrically succinct than within the closing lines of this song – the foreign military presence, cultural imperialism, disregard for our indigenous culture and the environment – where all of us are too busy to give a damn as the Oils provide a defiant proclamation on where they stand:

“Flat chat. Pine Gap. In every home a Big Mac

And no one goes outback. That’s that.

You take what you get and get what you please

It’s better to die on your feet than to live on your knees”

Maralinga was one of the earliest songs to address the hidden nuclear testing in South Australia during the 50’s and the devastating impact on the local indigenous population:

“And the grass became granite

And the sky a black sheet

Our bed was a graveyard

We couldn’t feel our blistered feet

And the moaning and groaning and the sighing of death

And the silence that followed

The album’s saddest and most poignant reflection then turns its gaze on our future as Garrett sings “I’m gonna wait till we reach the sky” until we’re “boxed in like candles” with “polar bear pride” before “turning to terror as the script is read out” on Tin Legs and Tin Mines.

When you read through the lyrics on 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 it’s apparent that this album was a turning point in Midnight Oil’s political activism. Although they had previously addressed a number of concerns on their earlier albums it wasn’t until this one where that vision manifested itself so clearly. Later that stance became proactive when Peter Garrett fronted the Nuclear Disarmament Party (where he came within a whisker of securing a seat in the Australian Senate); along with being an outspoken advocate for the environment (the Australian Conservation Foundation, Greenpeace); and ultimately as a member of the House of Representatives with the Australian Labor Party.

The album closes with Someone’s Trying to Tell Me Something with one last brutal frenetic burst. The song is ambivalent in its message, but its sonic outro won’t ever be forgotten by anyone with a vinyl copy of the album. The LP was recorded with a run out groove where the end of the song with its final refrain of “breaking me down” will play for an eternity – or at least until you stop the record if the turntable doesn’t have an auto return feature for the tone arm. The CD format holds the refrain for about 40 seconds, but it can’t match the impact of the vinyl version. The effect on hearing it on vinyl the first time was like a reverberating sting from a band who were never going to go quietly.

10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 never enjoyed the international success of later Midnight Oil albums like Diesel and Dust or Blue Sky Mining. 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 emerged at a time when we actively questioned US foreign policy and the very real prospect of nuclear war. It was a time when Australians began to consider their place on the world stage, questioning our alliances and the consequences of our government’s policies. In asserting who we were at that time we also began to question the actions of our past, particularly our treatment of, and relationship with, indigenous Australians. 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 explored those themes and as such remains an important part of our cultural and political landscape. It’s a shame North America ignored it because it’s Midnight Oil’s most sonically creative and politically energised record. It went on to become one of the biggest selling albums in Australian music history, remaining on the charts for a staggering 171 weeks. Listening back to it now for the first time in a long time it hasn’t lost any of its urgency or vitality. It’s a testament to both Nick Launay’s genius and the band’s willingness to take a huge risk in reinventing themselves that ensures its legacy remains intact.

Leave a Reply